Brian Wilkinson is the Activity Officer at RCAHMS for Britain from Above. The project is a four year Heritage Lottery Fund supported project run by RCAHMS and RCAHMW with English Heritage, and involves the conservation, digitisation and cataloguing of 95,000 negatives from the Aerofilms collection.

It’s an astounding statistic, but if you were to calculate the length of the coastlines of mainland Scotland and all her islands you would arrive at a figure of approximately 10,000 km. That’s a lot of coast, and so it’s perhaps unsurprising that the sea has played a pivotal role in the socioeconomic history of many Scottish communities.

The outreach work I have undertaken so far for Britain from Above has taken me to four very different coastal communities, each with its own special connections to the sea, and each with a unique set of stories. Stories about shipbuilding, fishing, trade, and defence have all been connected to the places visited. I thought I’d retell a few of these discoveries here.

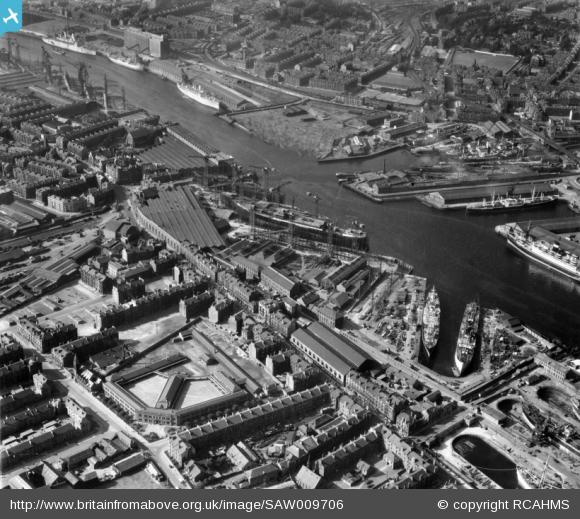

Govan

Govan was a major centre of shipbuilding throughout the 20th century, the centre of Clyde shipbuilding, and home to such famous yards as Harland & Wolff and Fairfield. Although today there are few remaining signs of this industry, people’s memories of it and pride in their community are still strong.

Working with members of the Govan Reminiscence Group, and the Fairfield Heritage Project, we have begun to create digital stories to document people’s experiences of living and growing up in Govan. These stories have included cherished memories of family camping holidays to the countryside, away from the noise and clamour of the burgh; recollections of moving into one of the first social housing schemes (complete with inside toilets); memories of a devastating storm, which blew out the lights and caused great damage to Govan in the winter of 1968; and even a story of playing football against a young Sean Connery who was filming at one of the shipyards! More sessions are planned to record further stories from members of the community, and we hope that they will be used at the Fairfield Heritage Centre to help illustrate life in the recent past.

Cromarty

We held an introductory session to Britain from Above and the Aerofilms collection in Cromarty, a Highland burgh on the Black Isle, in order to introduce a local heritage project to our collection. Cromarty Homes and Heritage involves local people sharing their memories of buildings in the Black Isle town, using maps and photographs to recall stories about buildings that still exist as well as some that have been lost.

The Aerofilms images were particularly well received, as not many people had previously seen them. The Cromarty images were all dated to 1930 and are a great illustration of the burgh’s architecture, from the Georgian merchant’s houses to the Victorian fisher town, the icehouse, and the former ropeworks.

The images provide a snapshot of Cromarty between the World Wars, and hold some amazing detail of daily life in a coastal town, for example fishing boats beached on the shore together with salmon nets hung out to dry.

Records of Cromarty’s role in the First World War were also remembered. One workshop participant recalled the Royal Naval Air Service seaplane base, and many others identified military buildings around the town. The Cromarty Firth was an important anchorage for the fleet and other photographs showed fortifications and former defence works to protect the ships from attack. Perhaps one of the most interesting discoveries was an image showing practice WWI trenches on the outskirts of the town, including one set which were previously unknown.

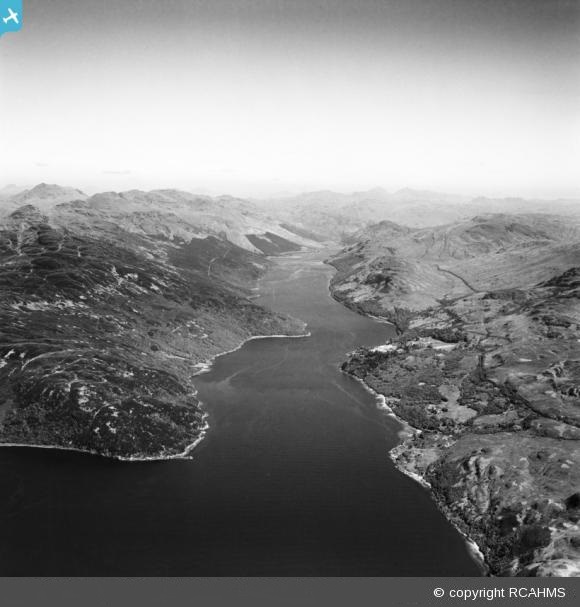

Arrochar

Arrochar is a rural village at the head of Loch Long in Argyll. It marks one end of an isthmus separating the sea loch from the freshwater Loch Lomond. According to the sagas, in 1263 Norse raiders carried their boats from Arrochar to Tarbet to go raiding on Loch Lomond.

Arrochar was home to LochLongTorpedoRange, which operated from 1912 to 1986. The torpedoes were originally produced further down the Clyde in Greenock, and later on in the former Argyll car factory in nearby Alexandria.

I visited Arrochar to deliver a workshop to the over-60s computer club, and had a fascinating day finding out people’s stories about life on the west coast of Scotland. Bowling harbour and the paddle steamers which were moored there had a special place in many people’s memories. Day-trippers and holidaymakers would take trips on the steamers ‘doon the water’ from Glasgow, to resorts on the River Clyde like Rothesay, Dunoon, Millport and Largs.

The harbour at Bowling no longer houses steamers, but the hulks of many former vessels can still be seen there.

Stonehaven

Work will begin shortly with the 1st Stonehaven Cowie Airscouts in Aberdeenshire to investigate their town and use the Historypin website to create a virtual tour. We hope to uncover stories old and new about Stonehaven from the local community. This is a particularly interesting project as the Airscouts were established by Baden Baden-Powell, an aviation pioneer and inventor of ‘man-lifting kites’! We are planning to undertake a kite photography session with the airscouts to create our own aerial photographs of Stonehaven and the magnificent Dunottar Castle.